A New Work in an Old Cinema

James Lingwood on Coronet Cinema, 2002

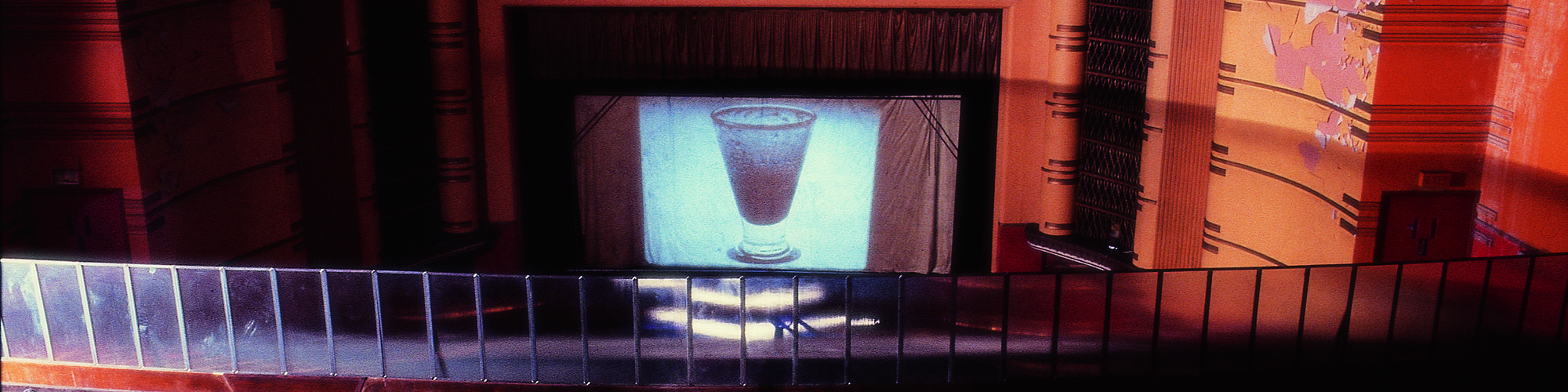

Melanie had decided that she wanted to make a new work in an old cinema. The scale of the cinema was important - it needed to be somewhere with a sense of grandeur. The Coronet gave a very strong sense of a cinematic experience before the age of television, when cinema going was a kind of communal, collective activity.

It felt as if the work was moving the viewer through the space (rather than the artist directing the viewer). The movement was always upwards, up the stairs fron the foyer into the auditorium. On entering the auditorium, the immediate view of the image was disrupted by a ribbed glass screen, which was too high to see over. So you were compelled to move upwards again, to see over the glass screen. Only when you had ascended right to the top of the upper circle could you see the full projected image.

Not for the last time, the work came together at the last moment, when the time-lapse 16mm reel arrived. It wasn't until Melanie showed me the rushes of this very slow evaporation that I understood how the whole project would work. Sometimes it's important not to ask too many questions whilst an artist is working through their ideas.

Perhaps it's worth repeating the Andrei Tarkovsky quote that Melanie had put in the leaflet. "Why do people go to the cinema? What takes them to a darkened room where for hours, they watch the play of shadows On a sheet? I think what a person normally goes to the cinema for is time: for time lost or spent or not yet had."

Like a fragmented Film

James Lingwood on Annette, 2002

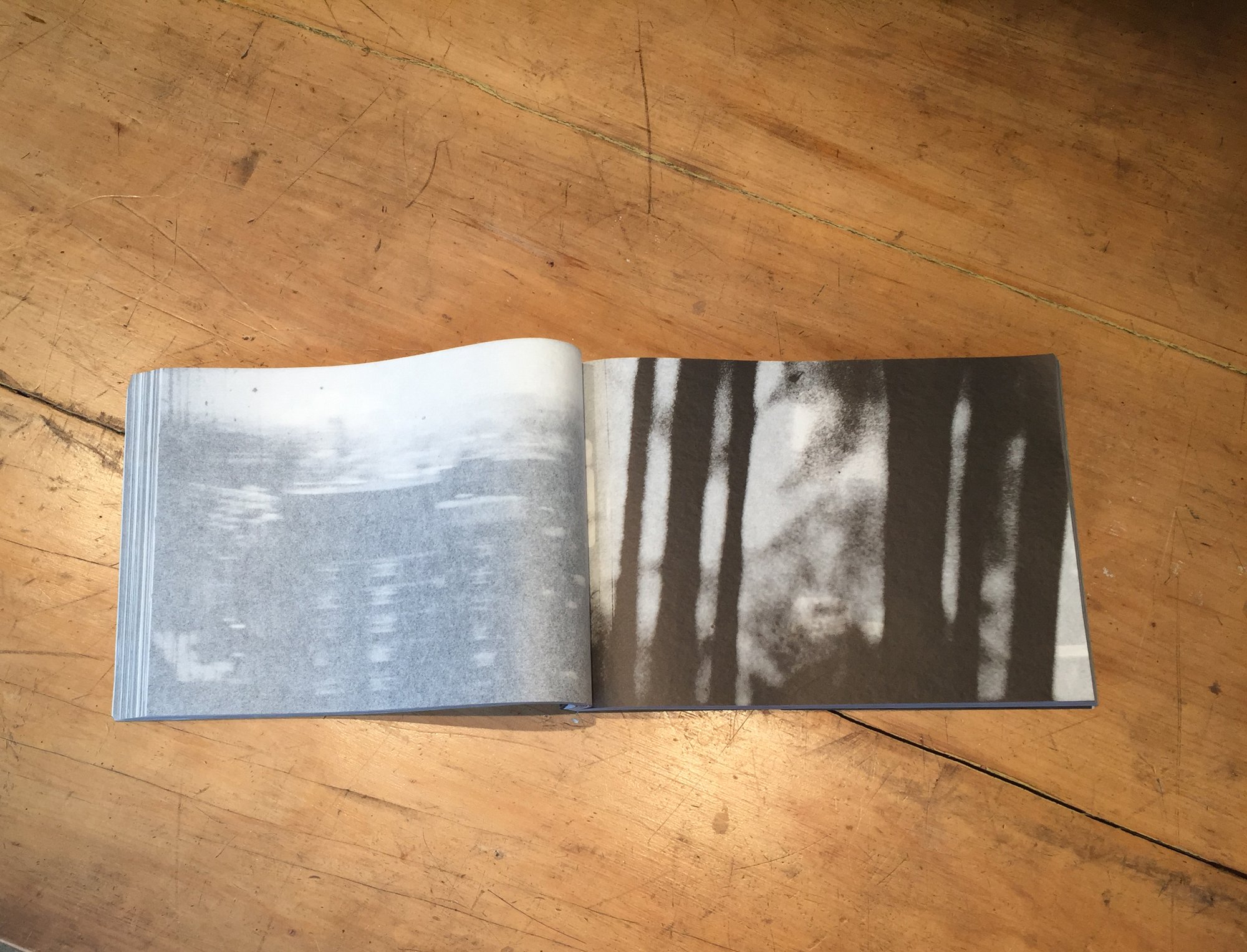

Working on the book project Annette with Melanie and Robin Klassnik from Matt's Gallery was slow in an enjoyable way. The long deliberation about paper and sequencing. The flood of images, all taken from her Super-8 films, overlaps and repeats, like a fragmented film.

Annette was an important project for us because it was the first time we had worked with an artist to try and find an equivalent – in the form of a book – for the experience of an installation. This collaboration persuaded us to make publishing an integral part of Artangel's activities, and we've continued to work with artists to make particular books and videos where possible. The fact that the book often appears some time after the initial project has disappeared creates an interesting space for a different kind of collaboration.

Image: Coronet Cinema, 1992. Photograph: Stephen White.

Melanie Counsell

Melanie Counsell is a leading British artist who creates temporary transformations of unusual environments and unoccupied buildings. Her works are remarkable for their economy of means and their poignant engagement with feelings of absence and loss. She has exhibted internationally, and was also awarded residencies at L'Ecole National des Beaux-Arts, Bourges, the Cartier Foundation, Jouy-en-Josas, the Sargant Fellowship at the British School at Rome and a 2009 residency at Cove Park, Scotland. She was shortlisted for the Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award in 1996 and was previously awarded the The Arts Foundation Award and the Whitechapel Artists Award. She currently lectures at the Slade School of Fine Art.

Image: (left) Coronet Cinema, 1993, photograph: Stephen White, (above) Melanie Counsell, photograph: Stephen White.

Annette & Catalogue (1998)

Annette documents Melanie Counsell’s spanning seven years and stands as a work in its own right. Comprised of images taken from Counsell's films, as well as documentation of works in situ, the book presents a flood of black and white images, not unlike a fragmented film. Printed on transparent paper creating an overlap of images as diverse as clouds, drain pipes, buildings and wine glasses.

Catalogue, published as a companion volume to Annette, presents the first published survey of the artists work, structured around approximately a twelve ‘chapters’ encompassing the development of Counsell’s work over eight years, ranging through her work made for both galleries (including Matt’s Gallery and Galerie Jennifer Flay, Paris) and more unorthodox venues.

- Binding: Annette is bound without covers, protected by a purpose-made polystyrene container. Catalogue has a soft cover in black and white, perfect bound and thread sewn and is supplied in the container alongside Annette.

- ISBN: 0 907623 28 X / 0 907623 29 8

- Pages: 264 (Annette) / 76 (Catalogue)

- Edition 500

- Dimensions: 205mm x 295mm

- Design: Phil Baines

- Published by Artangel, London and Matt’s Gallery, London

The grainy black-and-white image of an aperitif glass, placed against a blank ground, one-quarter-full of a dark fluid, filled the screen. And that was all. Nothing moving. Nothing changing. It was clearly a cinefilm - but it seemed to be a cine film of a still photo. — Rob Legg, The Independent Magazine, 10 April 1993

Selcted Press

Physically manipulated by the very nature of the place, the obscuring screen, the lighted gangways, and the evidence, visual and aural, that something is going on, the audience is led towards the very point from which a cinema film would normally be projected. What holds us is the acknowledgement that what we are witnessing is a rudimentary narrative structure that shadows the cinema’s current status – an emptied-out vessel with leavings – and which is reanimated and enlivened by renewed imaginative engagement. In some ways, what one is looking at is not very much at all. But, should one care to accept it, what is on offer is much more. — Michael Archer, Art Monthly, May 1993.

Time lapses without us being consciously aware, reflecting the spectators as they would have sunk into a film. The liquid condenses as the point of the building's dereliction compacts its own emotive history into one capsule of time. Counsel makes a complex reference to this history through the projection, representing a continuous series of perpetual presents.— Womens Art, May - June 1993

It left one to contemplate the Deco features of the building and other members of the audience and served as a reminder of an extended experience of time in relation to entropy and decay. The inaccessible space behind the glass screen provided series of devices – the ability to imagine and surmise about audiences of the past; the desire to be part of changing over the reels, a wish to engage more directly with the work and the building; the frustration and seduction of the unseen. — Helen Sloan, Creative Cinema, June - July 1993.

It was like the experience of being in a cinema before the show starts, and you keep thinking the lights are dimming, but they're not. By this stage the fluid-question had become totally absorbing; the interaction between spectator and screen was, whatever else, unquestionably intense. Again, we asked the usher. He told us, wait. The film would end, be re-wound, start again from the beginning. Then we could draw our own conclusions.— Rob Legg, The Independent Magazine, 10 April 1993.

Who made this possible?

Credits

Artangel is generously supported by Arts Council England, and by the private patronage of The Artangel International Circle, Special Angels, Guardian Angels and The Company of Angels.